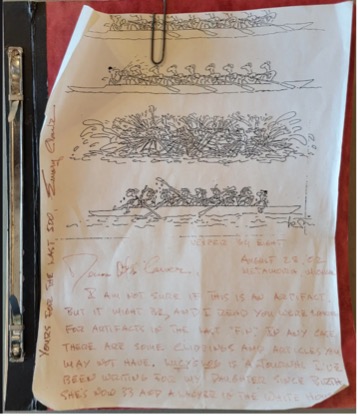

1964: A Motley Crew’s Olympic Quest

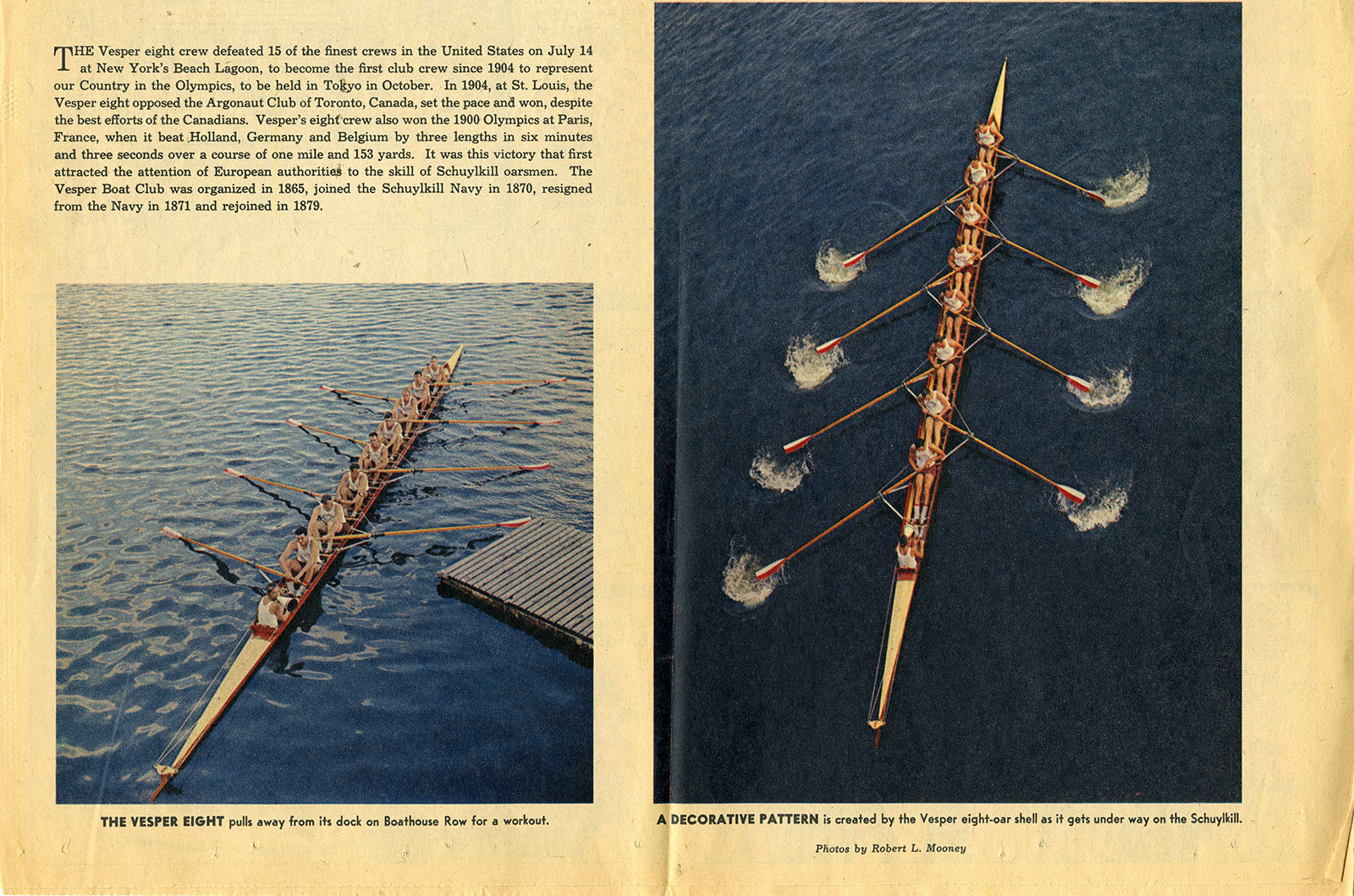

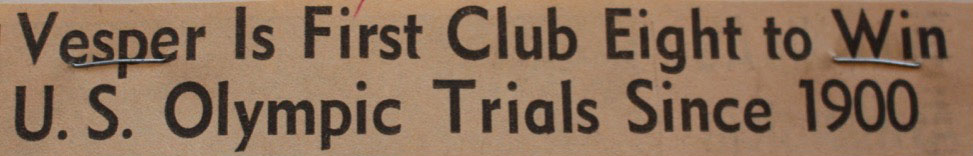

John B. Kelly Jr. had a dream. For 60 years, only college crews had represented the United States at the Olympics in the eight-oared boat. Why couldn’t the Vesper Boat Club trounce those kids and be the ones to go to Tokyo for the 1964 Olympics?

Kell, as everyone called him, came from an Irish immigrant family that had parlayed hard work and luck into fairytale fame. His father, John B. Kelly Sr., was the greatest sculler of the early 1920s, winning gold Olympic medals in 1920 and 1924. Kelly Sr.’s daughter – Kell’s sister – was Grace Kelly, the actress who became the Princess of Monaco. Kell himself was a champion rower, winning numerous international medals.

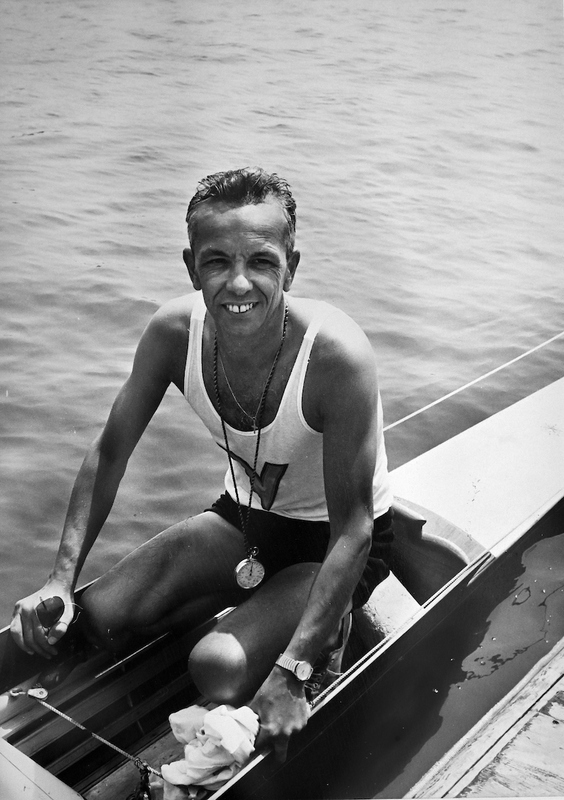

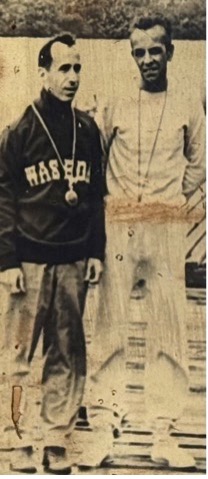

At the 1956 Olympics in Melbourne, Australia, which took place just after the Soviet Union invaded Hungary, the Hungarian crew defected. Kell, who won a bronze medal in the single sculls in Melbourne, was impressed by their coxswain, Robert Zimonyi. Kelly invited him to Philadelphia to cox at Vesper. No matter that Zimonyi was then already nearly 40 years old.

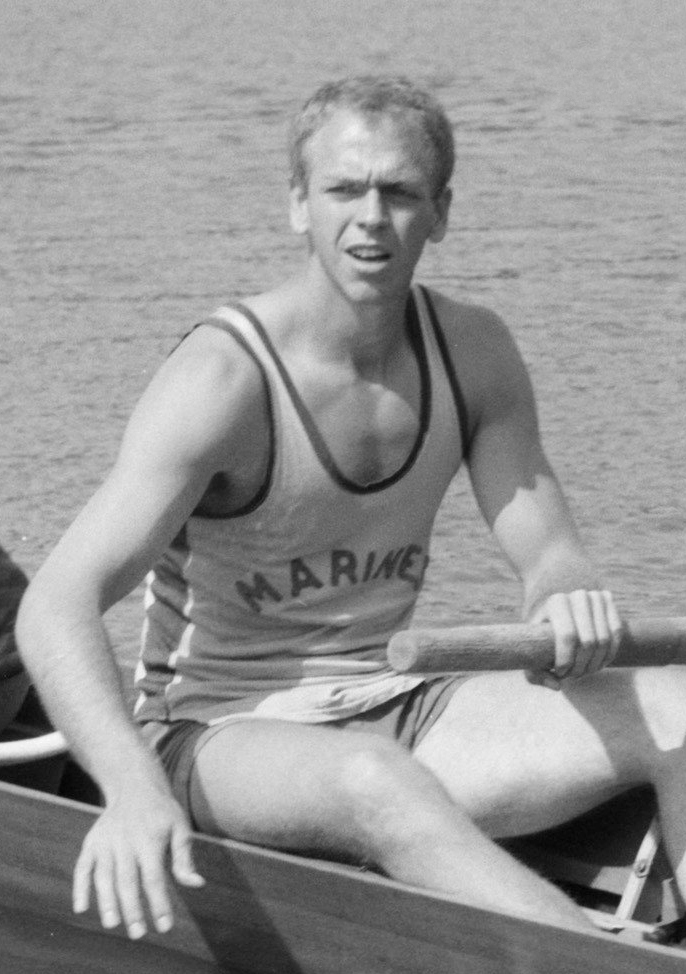

The Amlong brothers – Tom and Joe – had learned to row as kids while their father was stationed with the Army in Belgium. They, too, had a dream: competing in the pair in the 1964 Olympics. They saw Vesper as a premier training venue. Kell saw them as critical to the team he was assembling. He wrote letters to the military, where Joe was a lieutenant in the Air Force and Tom a lieutenant in the Army, arguing that these men would better serve their country training for the Olympics. With a tough, take-no-prisoners attitude, the Amlongs arrived at Vesper in 1963, not at all interested in rowing in an eight.

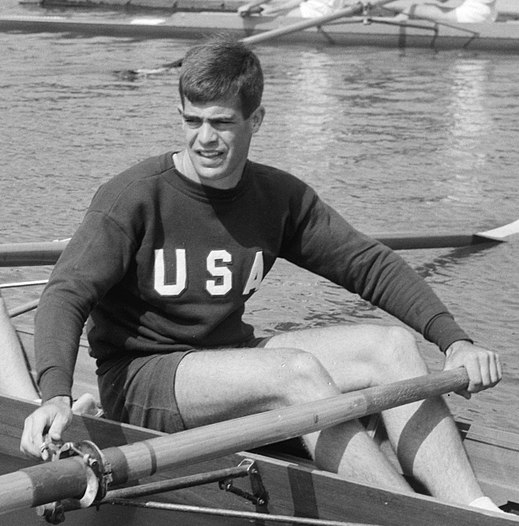

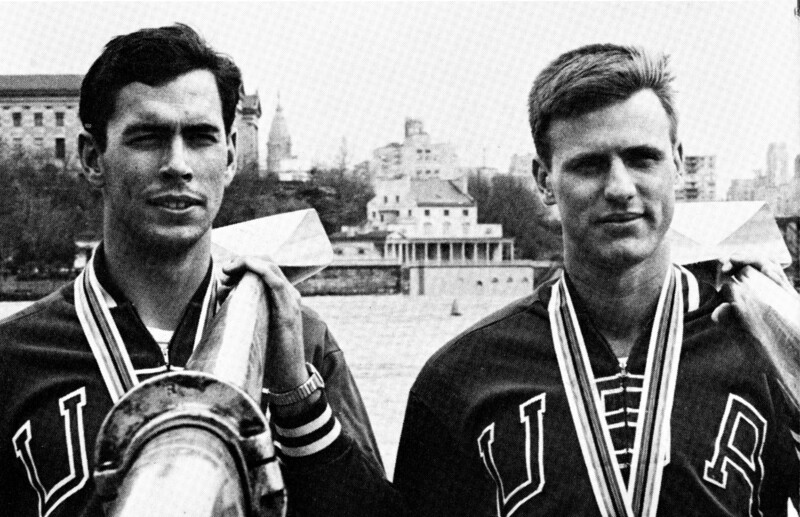

Emory Clark was stationed in the Philippines as the United States was entangling itself into Southeast Asia when he got a letter from rowing buddy Boyce Budd. Both had rowed at Yale University and had lost to archrival Harvard. Years later, the loss still pained them. They wanted a rematch. Emory petitioned Marine brass to relocated to Philadelphia to train for the Olympics. He ended up at Vesper serendipitously because the club offered him a row the very day he arrived in town. Boyce joined him there. Their goal was to compete together in the pair, defeat Harvard, and go on to glory.

Hugh Foley, at age 19, had transferred from Loyola in California to La Salle University at the recommendation of his crew coach, who saw bigger opportunities at Vesper for the talented rower. In Philadelphia, Foley convinced his classmate Stan Cwiklinski to drop La Salle rowing and train with him at Vesper instead. The two college students would be by far the youngest members of the crew that Kell was beginning to assemble.

The men who had gathered so randomly at Vesper trained hard through the harsh early months of 1964. Emory Clark, in his diary “Lucy’s Log,” wrote about the “dark cold mornings of February.”

“Bare feet are cold on the wet dock, wind drives through your sweat shirts as you put the boat in and rain goes down your neck…Dark when we came in and still nasty. Wonderful…pray that the warm weather will see an end to our aches and pains.”

Bill Stowe, 24, was another driven rower who showed up at Vesper that March. Stowe, who had rowed at Cornell (where he, too, had lost to Harvard) had been a Naval lieutenant stationed in Saigon when Kell wrote to him. If Bill was willing, he would ask the Navy to bring him home to train. Coach Allen Rosenberg immediately positioned him as stroke.

“Bill pulled as much or more water than most six men.” – coach Al Rosenberg

Bill Knecht, Kell’s longtime doubles rowing partner, also began to train seriously at Vesper in the spring of 1964. No matter that Knecht, then 33, had six children, was running a sheet metal business, and had to commute a half-hour from Haddonfield, N.J. to train on the Schuylkill River. “He wasn’t a huge guy, but a technique guy. He knew how to enter the water perfectly. You didn’t have to tell him anything,” recalled coach Dietrich Rose, noting that for an elite rower, Knecht’s age was “unusual.”

The would-be Olympians that Kell had pulled together from various corners of the globe mixed with each other like oil and water. The Ivy League Yalies were shocked, shocked by what they saw as the boorish behavior of the Amlong brothers, who routinely called the others “pussies.” Joe, newly married, would arrive each morning, boasting about the previous night’s gymnastics. Bill Knecht had too many work/family responsibilities to get involved in the personality clashes. The kids – Stan Cwiklinski and Hugh Foley – awed by their elders, just tried to stay out of the fray.

“There were times when I felt like a wild animal trainer with a chair and a whip to get the beasts in line and to do what was needed.” – coach Al Rosenberg

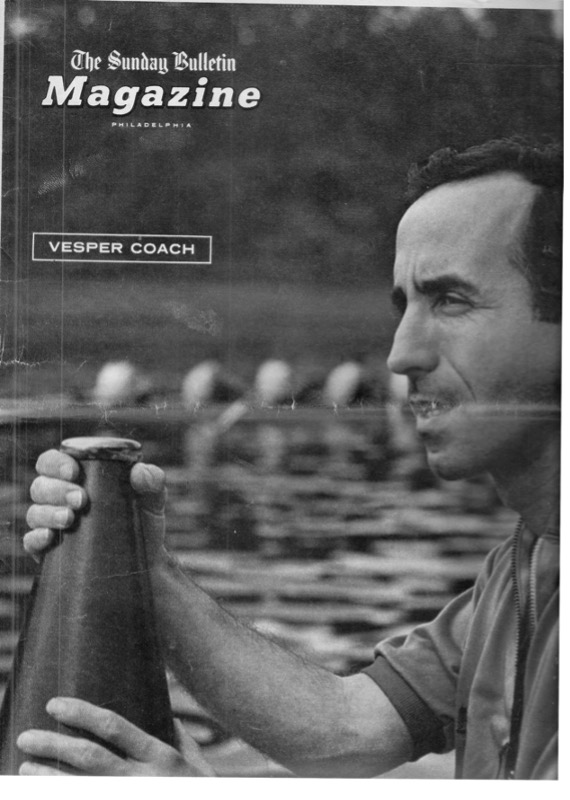

Vesper’s coaches had a more symbiotic relationship, though one was German and the other a Jew. Sidelined by the famed Ratzeberg Rowing Club for the 1960 Olympics, Dietrich Rose moved to Philadelphia. He brought with him to Vesper the German club’s rigorous interval training program, which involved weight lifting and running. Al Rosenberg contributed leadership skills and the insights of a “master psychologist, ” said John Lehman, who later became Secretary of the Navy.

“You had Rosenberg and Rose as the coaching team. And I swear … all would not have happened had those two not formed such a perfect partnership.” – Emory Clark

A turning point for the Vesper Olympic hopefuls was the American Henley on the Schuylkill River in June 1964. The Amlong brothers, who all winter had refused to step into the eight, lost their pairs race. Conceding that any possibility for them to get to the Olympics now lay in the eight, they quickly agreed to row with the others.

“The four of us [Emory and Boyce and the Amlongs] co-existed in the boathouse and were careful not to clash on the river where we had a good deal of respect for each other.” — Emory Clark’s diary

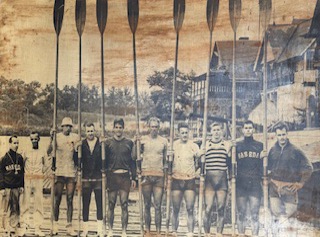

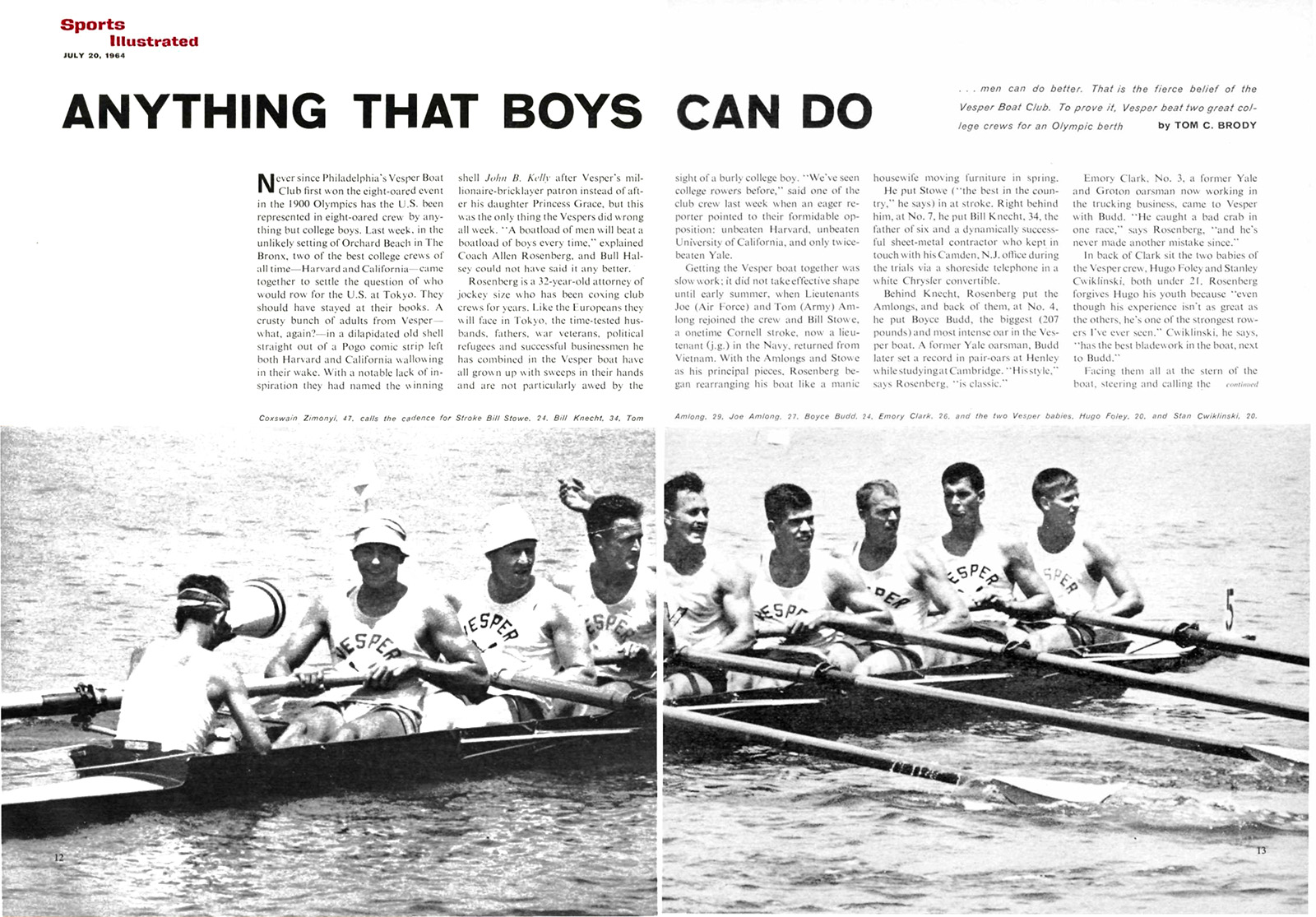

After months of tough training, a fired up Vesper crew in July 1964 arrived at Long Island’s Orchard Beach for the Olympic trials. They were a disheveled bunch with no team uniforms and an abundance of attitude. The press, calling them “old men” and a “motley crew,” had placed their bets on undefeated Harvard, coached by the renowned Harry Parker.

“The college trained oarsmen on the shore were flabbergasted at this mess called the Vesper Boat Club, but we were loving it, throwing them off, It was a fun psych job.” – Bill Stowe in his book, “All Together” (available on Amazon)

At the final race of the Olympic trials, the Yalies –Boyce Budd and Emory Clark– were hell bent on beating Harvard. “I wanted to row them down and then blow them away. I wanted to crush them,” said Emory. “I know Boyce felt the same way – he had never beaten Harvard in four years at Yale.”

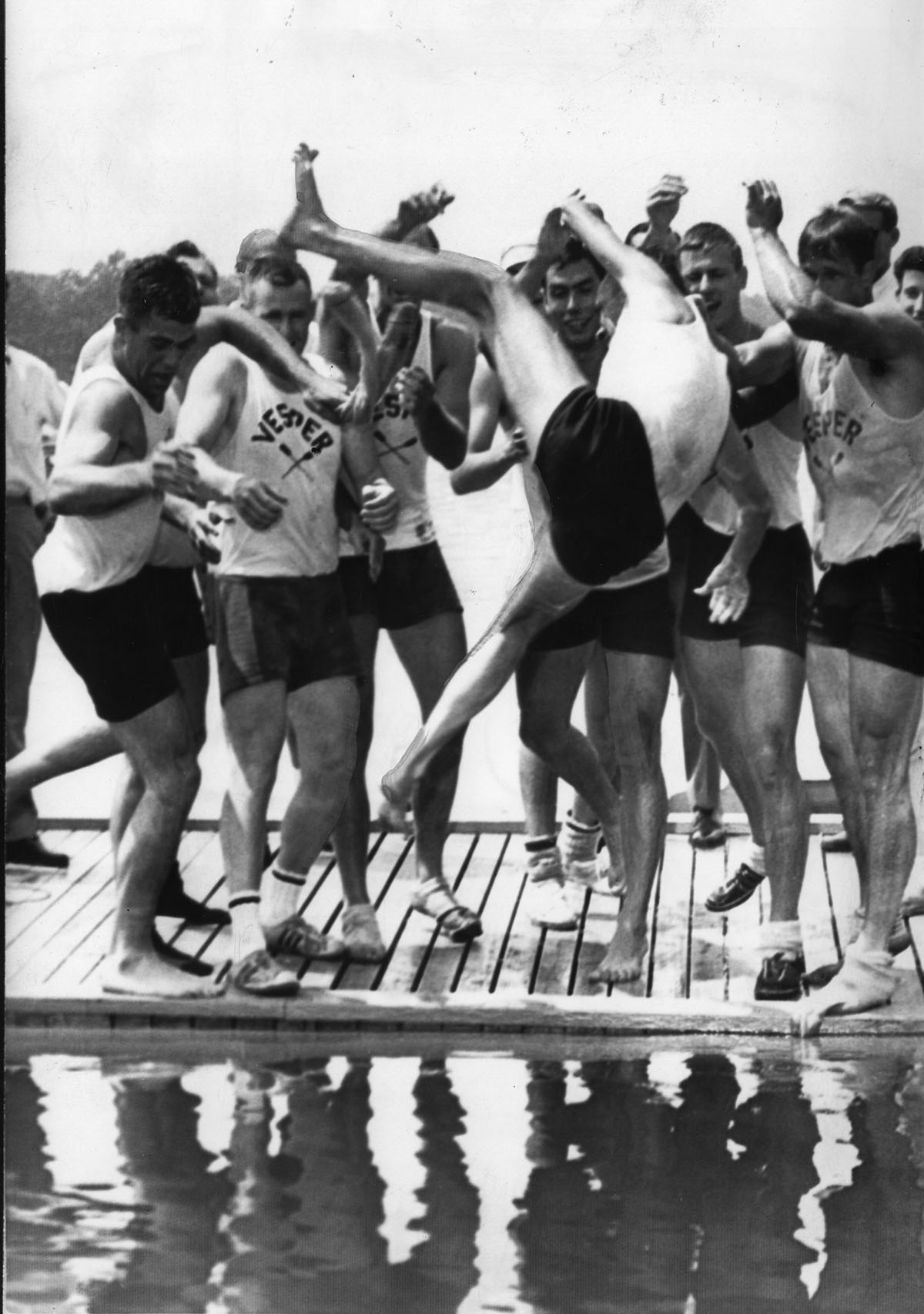

After Harvard called for a power 10, Vesper coxswain Robby Zimonyi called for a 10 as well. Their shell exploded forward, finishing more than a boat length ahead of their vaunted rival. While the exhausted Harvard men collapsed over their oars, the powerhouse Vesper, appearing unfazed, continued rowing past the finish line.

“A boatload of men will beat a boatload of boys every time,” coach Al Rosenberg told Sports Illustrated.

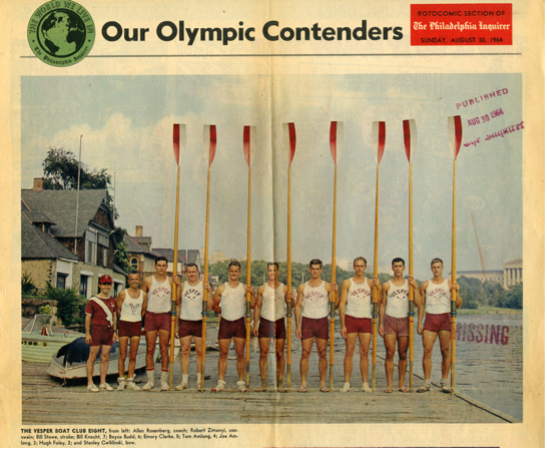

Back home, sports-crazed Philadelphians suddenly were rooting for a sport and a team they had previously not paid attention to. The Philadelphia Inquirer devoted significant ink to the Vesper crew.

Ominously, the Vesper crew arrived in Tokyo in October 1964 with Boyce Budd just recovering from mononucleosis and Stan Cwiklinski felled by the flu. They faced eights from 14 countries, including Germany’s Ratzeburg crew. Vesper lost to them in the repechage. Nonetheless, Kell was ecstatic – the Ratzeburg boys were writhing on the dock at the end; the Vesper men were merely exhausted. On race day, October 15, there were more concerns. The wind was high and races were delayed and Dietrich Rose had discovered a partially broken ball joint on their boat.

“Êtes vous prêt?” said the starter as the sky began to darken in the wind-delayed final. Sixty seconds later, coxswain Robby Zimonyi called out in his Hungarian accent: “Vee are in third place.” By 1,000 meters, they had passed the Soviets and were gaining on the Germans. Then near catastrophe: At 37 strokes a minute, Emory Clark’s blade slapped a wave and the grip spun in his hands. Boyce Budd, sensing Emory’s missed stroke, began to pray. With 500 meters to go, flares burst along the waterway and Hugh Foley, rowing without his glasses, thought they had lost. Then Robby yelled, “Let’s go boyz!! Vee are vinning.” They streaked in 1¼ boat lengths ahead of the Germans.

Returning home, the Vesper 8 were feted with parades and citations.

Read more about the Vesper 8

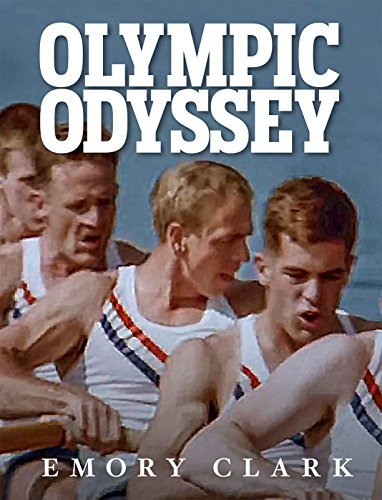

Winning gold was so central to the lives of the men of the Vesper 8 that two of them wrote books about the experience.